Philosophy of art

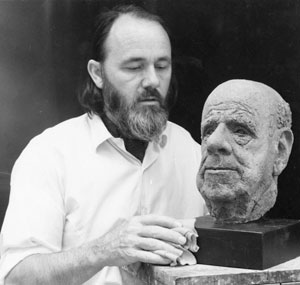

Artist with 'Portrait of an Old Man'

According to Osborne, there could be no objective criteria applied to art, except that of the artistic and technical ability of the artist. For him, the study of form, and of the function of life, were the key purposes of art. In a typical comment, he said that the move away from 'form' that abstractionism, especially constructivism, necessitates, negates the essential qualities of human life. Osborne would claim that the focus on a particular inanimate object may temporarily reflect the current preoccupations of a society, but, ultimately, these are transient and irrelevant; for example, the means by which heat is generated, be it by a naked flame or a radiator, is not of ultimate interest to the artist, it is that a person stretches out their arms to the heat, the functional act that creates a form, which endures throughout time, that needs to be expressed in art.

Based on this belief, Osborne's artistic career developed along two distinct, but interlocking, paths: through his production of art works; and through his development of the unique, figurative sculpture course at Stafford College. Osborne's practice in the conduct of both does more to reveal his philosophy of art than anything else.

In terms of Osborne's art work, this can be broadly divided into three strands, which all reflect 'the form' in different ways. These strands of work were started at different times in Osborne's career, but overlapped with one another.

Firstly, the figurative work, which he prioritised during the 1940s, focused on the human form, and continued throughout Osborne's career. His major works in this mode include: the submission for the Unknown Political Prisoner (1953); portraits of Peter Hope-Evans (a member of Medicine Head), Bjorn Borg, and Indira Ghandi; and 'Girl with Cello' which was exhibited in Covent Garden in 1982.

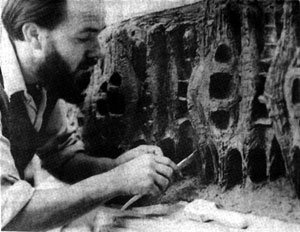

Artist modelling 'Victims at the Wall'

Secondly, towards the end of the 1950s, Osborne started to develop a series of non-figurative works in wood and resins, which found inspiration from natural forms. Although the range of work in this non-figurative series is striking and thought-provoking (in fact, he referred to them as "mindforms"), Osborne ultimately found the abstract too restrictive to express the fundamental characteristics of human life.

Thirdly, in the latter phase of his career, Osborne turned to the animal world for inspiration, carving and modelling elephants, buffalo, and wolves, amongst many others, sometimes in a naturalistic manner, and sometimes in a somewhat stylised non-western manner; reflecting both his early models and influences from his Indian period.

In addition to his output of art, Osborne created one of the few figurative sculpture courses in the U.K., and ran this course until 1990. In part, the course was a reaction to the prevailing focus on 'conceptual' issues, at the expense of technical development, in art education. In another part, it reflected Osborne's distain for many of the more restricting aspects of the academy (e.g., teaching by committee, inspection by the unqualified, and tick-box regulations), perhaps developed as a result of his earlier army experiences. Like many young men of his generation, Osborne's time in the army engendered in him a scepticism about the competences of the 'officer class', and the 'establishment' as a whole, that would be manifest in that generation's later development of anarchic entertainment, such as The Goon Show. In Osborne's case, it served to plant the ideas about exactly how the education of art should be handled. In addition to the unique focus of his course, the style of teaching developed on this course was also unique; called the "Atelier Method" by Osborne, as it involved students learning directly from Osborne's own work, which was conducted alongside theirs; a typically bold statement of ability, and one from which less-able artists would shy away.

Not surprisingly, given such views, Osborne had a healthy disrespect for contemporary 'conceptual artists', whose work had neither technical ability, nor had their ideas any logical substance or relevance, failing, according to Osborne, as both art and philosophy. Osborne gave similarly short shrift to critics of art ("Eunuchs, who know everything about it, but can't do it!"), and, when courted by the critic, Herbert Read, at the peak of his London-period fame, replied: "I don't drink with critics!", somewhat needlessly, as Osborne did not drink much at all.

The values encapsulated by his art works and course, the focus on form and study from life, reflected and captured Osborne's views on the nature of art in general. These views have, in turn, influenced several generations of figurative and non-figurative artists, who studied with Osborne, and whose own works and teachings still reflect these values, and of whom Osborne was immensely fond and proud.